Sixpence None The Richer

TONY LEVIN

Bass player Tony Levin has maintained this website since 1996, giving behind the scenes views of life on the road and featuring his photographs from stage and on tour.

His most notable bass playing albums and tours have been with: Peter Gabriel, King Crimson, John Lennon, Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, Alice Cooper, Buddy Rich, Peter Frampton, Gotye, Carly Simon, Judy Collins, Paula Cole, Chuck Mangione, Steven Wilson, James Taylor, Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe.

Solo albums: World Diary, Waters of Eden, Resonator, Pieces of the Sun, Stick Man.

Collaborative groups: Bruford Levin Upper Extremities, Bozzio Levin Stevens, Liquid Tension Experiment, Levin Torn White, Levin Minneman Rudess, Levin Brothers.

Levin is currently a member of the bands King Crimson, Peter Gabriel Band, Stick Men, Levin Brothers

Books published: Beyond the Bass Clef, Road Photos, Crimson Chronicles vol 1. and (coming soon) Fragile as a Song.

Born in Boston, June 6, 1946, Levin grew up in the suburb of Brookline, starting playing upright bass at 10 years old. In high school he picked up tuba, soloing with the concert band, and started a barbershop quartet. But he primarily played Classical music, attending Eastman School of Music in Rochester, NY, where he had the chance to play under Igor Stravinsky and in the Rochester Philharmonic. Also at the school was drummer Steve Gadd, who introduced Tony to jazz and rock, leading to his trading in his upright for a Fender bass, later moving to New York, joining the short-lived band Aha, the Attack of the Green Slime Beast, and becoming a studio musician.

Having played on many albums in the 70’s, Levin jumped at the chance to tour with Peter Gabriel in 1977, switching to Music Man basses, which he still favors, and learning the Chapman Stick, which he played extensively in King Crimson from 1981, and led to his starting the band Stick Men.

In 1984 Tony released Road Photos, a collection of black & white photos taken during his travels with Crimson, Gabriel, and others. Soon following was the book Beyond the Bass Clef featuring stories and essays about bass playing. Another photo book, Crimson Chronicles, volume 1, the 80’s contains an extensive collection of his b&w photos of life on the road with the band.

2016 is another year filled with creative output and concerts for Levin. Stick Men has toured the U.S. and will play in Europe in the Fall. The Peter Gabriel / Sting tour in Summer will be a notable one. Joined by Adrian Belew and Pat Mastelotto, Tony will host the yearly Three of a Perfect Trio music camp in the Catskill mtns of NY State. King Crimson will tour in Europe from September. A new album release from Levin Minneminn Rudess is coming, as is the album “Prog Noir” from Stick Men. And in June, a book of Levin’s lyrics and poetry, titled Fragile as a Song.

2021 With the drastic changes of the past year, much less touring, but in the Summer a new album was written and recorded by Liquid Tension Experiment, for Spring 2021 release. And Tony completed a large book of his touring photos through the years, Images from a Life on the Road. Tours this year are booked, but marked as “tentative’ at this point.

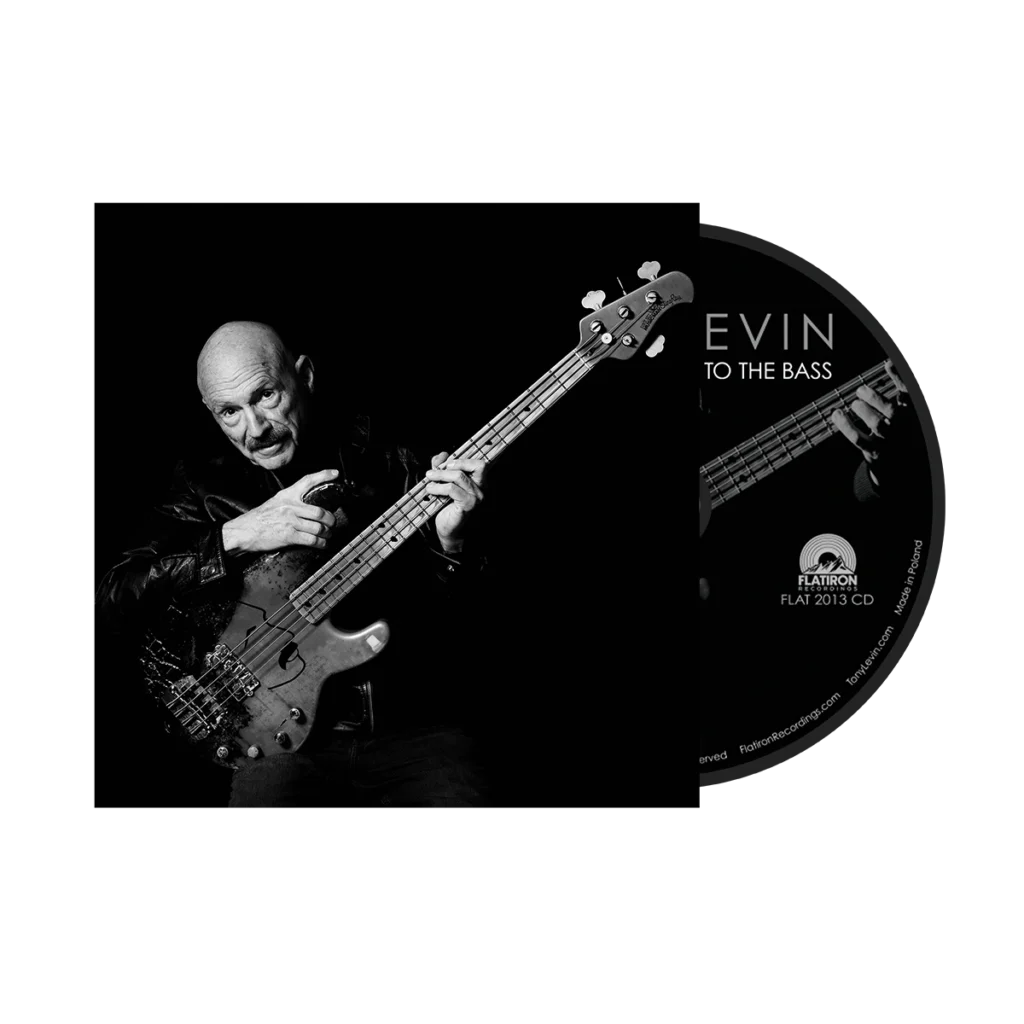

Album bio

Bringing It Down to the Bass

The name of the album is Bringing It Down To the Bass, so you know darn well Tony Levin is going to deliver some seriously killer licks on electric bass and the Chapman Stick. And you can bet there will more than a few tricky time signature changes and swift genre shifts.

Start to stream or spin the album and you’ll find songs of wit and whimsy and songs of power and profundity. Mostly instrumental tracks, a few others with vocals and spoken word. The sonic stew includes prog, jazz, thrash, a wee bit of classical, a whiff of barbershop quartet and you won’t be sure what’s around the corner.

And while it’s called Bringing It Down To The Bass – and that’s no lie – it’s not all about that bass. Levin’s seventh solo album, and his first since 2007, is a autobiography of sorts, with the themes drawn from Levin’s musical life. It features a myriad of collaborators from his half- century-plus on the road and in the studio with Peter Gabriel, King Crimson and many, many others.

“It could have been done a long time ago, frankly,” Levin says, of Bringing It Down To the Bass, “but it’s because of a problem I have, which is a very good problem to have. And that’s that I have a lot of touring and that’s what I love to do, playing live. It just didn’t give me much time at home to work on finishing the album that I’ve been working on for five or six years.”

“But,” he continues, “a year ago May, I looked at my schedule and saw a lot of touring with Peter Gabriel for almost a year and then in December 2023, there was a Stickmem tour – that’s one of my other bands – and then in January a Levin Brothers tour – yet another of my bands, with my brother Pete – and I said to myself, ‘If I take March, April and May off from any live playing and maybe even any recording for other people and really focus on this, I can finally get this album out.’ It could have happened ten years before if I had the gumption to turn down tours.”

Ah, yes, all those tours. (More later about one of those coming up this fall.) And albums. He’s played on more than 500, including 15 with Gabriel and 18 with King Crimson, counting live, studio and compilations.

Bringing It Down To the Bass was not, as you may have gathered, put together during one big session. It was stitched together – both live in the studio and done by sending tracks back and forth via email – over the past half dozen years. “Or maybe more” says Levin, trying to do the math. “I have not calculated but some of them are pretty darn old. Frankly, there were many more tracks than the 14 that were the final ones and gradually, as you do, I honed it down to the ones that I thought appropriate to this album. so somewhere along the line I forgot which ones were written when. Some of them, though, were written very recently. The duet with Vinnie Colaiuta on drums, on ‘Uncle Funkster,’ we finished two weeks ago.” (Meaning late May, 2024.)

So, what was appropriate for this album?

“I had pieces very much in the prog-rock vein and I had pieces that were based on the bass,” Levin says, “and somewhere around the middle of the record I made the difficult decision to toss the prog stuff – well, not toss it exactly, save it for another album – and the more I focused, I chose the kind of pieces that had to me a sense of unity to it in that it’s about the bass. Not songs with singing about the bass, but each song is either based on a bass riff or a bass technique that I then invited some great rhythm sections to play on.

“My basses do sound different. I wanted to write at least one piece with the funk fingers and I did that fingernail way of playing that I featured on one piece, and hammer-on technique on that first piece, ‘Bringing It Down To The Bass.’ I used to use that a long time ago and I hadn’t used lately since I got the Stick, which is designed to play with the hammer- on technique. That’s also a piece that has a rocking, really hot rhythm

section with Manu Katche, from Peter’s band. Also, maybe two or three times in the piece it breaks down and stops to just the bass playing different riffs and then Dominic Miller, from Sting’s band, comes in and solos or Alex Foster solos on sax.”

So, who is the audience?

“I never really gave it a thought,” Levin says, with a laugh. “It was ‘This is the album I want to make and I sure hope everybody likes it,’ but I never thought about who it would appeal to. I have fans who follow my music who are mostly or completely from the prog-rock genre. I think bass players would be interested in hearing it. And because I have an amazing assortment of great drummers, seven, so I would think drummers would be interested in hearing it.”

Some of the key tracks, discussed by Levin: What Tony says is in italics and my interjections or introductions are Roman – JS

Road Dogs

Usually, I have a musical plan and that’s the way the piece comes about but, in this case, not at all. I had this instrumental piece, this little guitar-like melody at the beginning and it went in different places and it went into a shuffle feel. It just wanted to go there and I was in that mode of writing where I’m letting the piece go where it goes. And while I’m playing bass on it and putting that together, a sound I always to use but hadn’t for a while was the fretless bass through a vocoder – a vocoder is a device where you say words and play an instrument through them – think Peter Frampton’s “Do You Feel Like We Do?” I thought “This is the chance to use it and I’ll mouth ‘road dogs.’ I thought I’d sing it where I’d try to sound like the bass with the vocoder. I spent time subsequently trying to get a good sound with the vocoder and it was terrible. I couldn’t get a sound where you could understand the words at all. However, there was a vocal I had done so I just left the vocal with undertones of my voice in a silly way.

At that point I added a few even sillier words about what we do on the road – “Ain’t nothing but lighting & rigging & soundcheck & gigging, packing & loading & driving & roading … Trucking & bussing & rigging & trussing, fixing & tuning & mixing & crooning.” I had the word schlepping in there too, but I decided to take that out because it’s so hard to understand. There’s a lot of consonants in the word schlepping. My bio title could be: Schlepping Didn’t Make the Cut.

Boston Rocks

It speaks, musically and lyrically, about the city I’m from. There’s very much two sides to the town. It’s a rugged, rough town in a way, especially revolving around the sports teams. A lot of success nowadays, not so much when I was a kid growing up. Yet, it’s home to universities and a rich history.

This is not one style of music. It begins with heavy rock and then I went into a progressive style, a B-section based on the Chapman Stick, where I tried to recite some poetic stuff about the historic, much more cultured side of Boston, and, frankly, I used quite a few JFK quotes that he had given in Boston. I enlisted Mike Portnoy to give me heavy drums – we’ve been in a band Liquid Tension Experiment for quite a while – and I love Earl Slick’s playing – we go back to John Lennon’s records and David Bowie stuff – and he really can rock out.

To wit, Levin shout-sings about Scollay Square (the old red-light district), Hah-vahd Yahd, the Garden, Fenway Park and Gillette Stadium, but also speaks this: “Born on the tide, midst the fens and reeds that wash and waver in still salted Back Bay, an audacious dream of a nation bound by common threads, fisherman and farmer, Yankee and immigrant, born to awaken the future that city upon a hill on which has never settled the dark dust of centuries.” The song moves from screaming metal skronk to a dreamy and idyllic pleasure zone.

Could it be a hit?

I tried to combine things a way musically that to me made sense but it’s exactly what you don’t want to do if you want to have an accessible single.

Floating in Dark Waters

Robert Fripp donated one of his distinctive soundscapes to this moody instrumental. I play sparse melody on the NS Electric Upright, and Jerry Marotta joins on percussion at the end. How did it come about? OK, way back when we toured with King Crimson a lot, there were a few tours this century where Robert would play a looping soundscape he would create before the show and the audience would hear it as they came in. He would make up a different one every day, maybe a half hour. Some nights when we were about ready to go at 8 – we always started at 8 – Robert said, “Tony, go out and play bass to my soundscape.” These soundscapes were often atonal, but sometimes they were tonal. We played many on stage, every night for years and it occurred to me then that it would make a very interesting piece on an album, just bass and soundscape. At some point I asked him for a soundscape, I don’t know how long ago. I put my head into the soundscape and played whatever notes came out of the bass.

Fire Cross the Sky

I wrote it a really long time ago. In the ‘70s, I used to live on the Upper West Side in New York, not far from Café la Fortuna. I would go have a coffee with my journal and I’d look up and see this shrine to John Lennon with all his pictures on the wall. And the idea for this poem came from all those coffees I had. Once in a while, to write, especially journals or poetry writing, I need to get away from home, But I don’t like to do it on the road either, so I’ll make a trip somewhere and I’ll just go to cafes and write.

I was on such a trip in Berlin for five days. I had the Stick with me and I was coming up with this very cool musical idea, which you hear in this song and somehow in the middle third of that, I was fiddling around with the chords and how I’m playing, it occurred to me what song would really fit well. Musically, it went into a quote from a classical guitar piece that I knew from a Paraguayan composer, Augustin Barrios, Una limosna por el amor de dios. Why that had to happen can be figured out when they open up my brain.

Usually, when I have those kinds of things, I’ll change it later or take it right out because I don’t want to be quoting a classical guitar piece, but it just seemed right and I thought that’s gonna stay. There are three elements to the song. I think it’s interesting harmonically; it’s an interesting Chapman Stick solo piece; and then when I attached it to the poem I wrote and I wanted to go into this beautiful melodic piece at the end.

In “Fire Cross the Sky,” Levin sings, “They could write his name in fire cross the sky, I wouldn’t mind / But it’s there inside his music I find the pieces of his soul he left behind.”

And then … in 1980, I ended up playing on John and Yoko’s Double Fantasy album.

On the Drums

It’s a name-dropping tribute to some of the many great drummers I’ve played with over the years. An utterly unique piece: An a capella male chorus – that’s multi-tracked me – sings a fascinating composition using names of the drummers. I tried to be brave and said, “Ok, I’ve got this song about drummers and it’s nothing but my voice.”

It starts with Jerry Marotta (repeated several times) and, among those I caught were Ringo Starr, Carmine Appice, Nick Mason, Phil Collins, Steve Gadd (also repeated several times), Andy Newmark, Lenny White,

four more Steves – Smith, Jordan, Ferrone and Martell – Bill Bruford (repeated several time), Billy Cobham, Mike Portnoy, Russ Kunkel, Manu Katche, Kenny Aronoff, Stewart Copeland, Rich Sullivan, Richie Heywood, ending appropriately (bookending, really) with Jerry Marotta’s brother, Rick Marotta. Oh, and listen for the nod to Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody’ when Terry Bozzio pops up.

How long did it take to patch together?

One doesn’t’ count the hours because one would question what one is doing. But I would guess, over the space of a year. I got that idea years ago and at some point, during the lockdown year, there were pieces of paper all over my large studio, little scraps of musical ideas of two drummers names who rhymed or who could fit somehow in the same kind of music, dozens of pieces of paper. Tying it together, that took a long time. And it was an act of love and respect.

The only words aside from the drummers’ names are the last three words “on the drums.” It was great fun. My stress in doing it was that I was going to leave out a drummer or two who are very important to me, who I played a lot with through those years. What you have to do often when you’re making a record like this is you have to take a deep breath and be brave and say “Ok, if I forgot somebody, I’ll apologize but I’m going to finish this piece anyway.” Frankly, I did a video of the piece, an early mix, and at the end I thanked the 20 or 30 drummers I forgot to put in.

What follows are (mostly) the notes Tony wrote about the remaining songs, songs not mentioned or annotated by the quotes above. Not sure, of course, how many of these songs you want detailed beyond what’s ^. – JS

Me and My Axe

An instrumental ballad, re-uniting some Peter Gabriel Band alumni, Steve “the Deacon” Hunter on guitar, Larry Fast and Jerry Marotta on drums. Melodic lead lines are shared by guitar and fretless bass.

Espressoville

Instrumental with Steve Gadd on drums, and a horn section, it starts out (and ends) with my espresso machine grinding and growling. A notable fingernail style bass solo in the middle, and a strong Gadd-driven shout chorus at the end.

Give the Cello Some

The NS Electric Cello is the centerpiece of this whimsical rocker, and the few lyrics speak about the cello, and my brother Pete on organ. Jerry Marotta is on drums.

Side B / Turn It Over

A barbershop quartet, singing about the experience (vintage now) of discovering the second side of an album. I’ve always liked barbershop quartet – I love the harmony – and when I was a kid in Brookline High School I had a working barbershop quartet. We would actually sing the morning greeting on the PA system at school. (I coaxed Peter Gabriel into using some barbershop arrangements on his first album and tour.)

Beyond the Bass Clef

Things change up after the “Side B” song. This almost classical instrumental features L. Shankar (Shakti, Peter Gabriel) on violin, Gary Husband (from John McLaughlin’s The 4th Dimension) on keyboards, Colin Gatwood (from the Houston Symphony) on oboe and me on cello, bass and Stick.

Bungie Bass

I got a rubber bass sound from my NS Electric Upright, and am joined on this instrumental by David Torn (from Everyman Band) on guitar and Pat Mastelotto (from King Crimson) on drums. I had played on Torn’s distinctive Cloud About Mercury album.

Artist bio

Tony Levin didn’t start out on bass. As a kid, he, like many, played piano at his parents’ behest. “You must learn to play piano and after a couple of years you must choose an instrument,” Levin recalls. “It was a culturally Jewish thing. After a few years of piano, I chose bass. I don’t know why. But it was a very good choice for me because I am still captivated by doing that exact same thing.”

A very good choice, indeed.

“How lucky am I to be doing what I wanted to do when I was 12 years old?” Levins says. “What’s changed is that I’m more grateful for it now. What hasn’t changed is I’m still trying to get better. I’m pretty good at it, but there’s so much to it and there are so many great bass players one hears playing amazing things, including very young bass players. So, I keep trying to up my game and be the bass player I feel I ought to be.”

Levin certainly made his mark prior to 1976. He played countless sessions including work with Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, Herbie Mann and Paul Simon – but it was that fortuitous meetup with Peter Gabriel and King Crimson leader Robert Fripp that helped catapult Levin to where he is now – and has been for decades. No one has served longer as a band member in either setting.

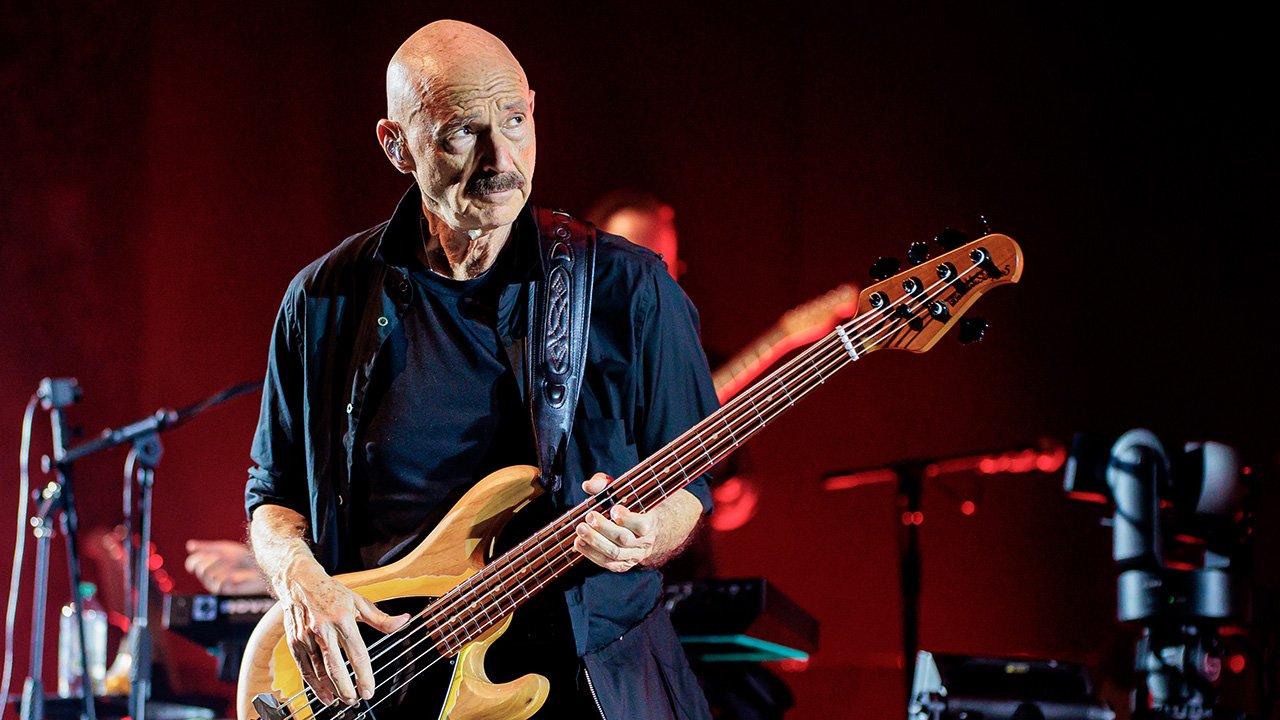

There is no more physically – and quite possibly musically – recognizable bassist in rock today than the tall, lanky man with the shaved pate and trademark mustache. On the occasion of his 78th

birthday on June 6th, he responded to the various well-wishers on Facebook by thanking his fans and noting his good fortune.

Though Levin prefers playing live to playing in the studio, he’s become a go-to session man for so many artists, famous and not. And why might that be?

“That’s a good question and I don’t have a good answer,” he says, “and it’d be pretty rare if you found me boasting about myself. What I know after all these years is the way I am: I’m not too inquisitive in a musical situation. Someone calls me and I listen to their music, whoever they are, whether they’re famous or not, and I’m just into the process of trying to find a great bass part for that. I’m so into it that I just don’t ask ever why somebody called me. Why? I almost never know.

“I never really thought of myself as a ‘studio’ player but someone who does a lot of records in a rhythm section. I guess one of the things you become OK with is working with a different process for each record.”

Levin’s career was already on an upward trajectory when he was summoned to work on Peter Gabriel’s first album, where he also connected with Robert Fripp. That brought him to another level.

“I’ve had some bad breaks, a few of them, but I’ve been very lucky and had some very good breaks,” Levin says. “One of them was in 1976 when Bob Ezrin, the producer, called me to come up to Toronto. He had used me with Alice Cooper and Lou Reed and thought I would be appropriate to do an album with this guy Peter Gabriel, whom I hadn’t heard of. I didn’t know about Genesis so I came into it with no experience of what Peter was and what he’d done on stage musically.”

Levin’s initial thoughts?

“Peter’s music was really unusual. He would play the songs for us on piano and I thought, ‘This is really different, I really like it.’ What I

remember was I was very interested in being introduced to this new kind of music that this young Peter was writing. It was very different from anything I had heard. I didn’t put it in that category of ‘progressive rock’ because I wasn’t very interested in genres. His chord structures and the way of going about writing a song was very different than anything I had run into. I thought it was fascinating.”

Peter had left Genesis and playing on that album playing guitar was Robert Fripp, whose music I didn’t know either. So, on that date, some day in July 1976, I met Peter and Robert and here I am 48 years later still actively making music with both of them. How amazingly special is that! The personal relationship and taking that journey of making music together, which changes if you’re making a lot of music, you learn a lot about each other musically.

“There were three guitar players, as Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner were also involved. We were all listening to this new music and we sat down trying to play it. Did I right away hear Robert and say ‘That’s amazing!’ No. I thought he was really good, but then, when I had time to focus on his playing, I thought that was really special. Obviously, we got along musically very well and not too long after than he asked me to play on his solo album, Exposure.”

And now, a little bit about life in King Crimson

“You sign up for King Crimson and you know you’re going to be challenged musically in a few ways. I don’t know how Robert knew this but jazz musicians had a way to signal the key of the piece before it starts – two fingers down means B-flat, one finger up means it’s in G- sharp, etcetera, and Robert knows this. Just as about we’re to go on, he wouldn’t tell me to play, he would just signal me with his fingers, the key for bass. Some nights he would hold all ten fingers in different directions and me being me I would take photos of that. There’s Robert telling me the key of this atonal soundscape he expects me to play to just a few seconds before. For a band with deadly serious music and is

deadly challenging, King Crimson, in all incarnations, had a great sense of humor. There was a lot of laughing and joking within the music and on stage and when we came off. That helps get through the tension of every night trying to create intense music that pushes you.”

Levin hails from the Boston area and as such is a New England Patriots fan. There was something instituted under former coach Bill Belichick called The Patriot Way. It’s a certain discipline, a way of looking at the game and its preparation. Might there be a King Crimson Way?

“Yes, indeed, there is a Crimson way,” he says. “I don’t think there’s much of a parallel between the Belichick-ian way and the Fripp way because Belichick is very exact and vocal about saying the way it is and Robert, in his unspoken way, has a Crimson way of doing things. We don’t have a big lightshow, a big production. The idea is, as in a classical concert, to watch the musicians and you’ll see a lot of personality from different guys. You’ll get to know them from watching them and there’s plenty of room for them to be themselves.

“It’s not like everybody is acting the same or is the same kind of person or musician. We rehearse a lot, including the day of the show and probably half the guys are rehearsing in their rooms. We’ll get to the venue at 1 and rehearse at 2 or 3. That’s a little unusual in a band of this maturity and guys that are technically able to play the parts. We find we need to be at our best to play the show we want to play it.”

Is there a future for King Crimson?

“I know better than to speak for Robert,” Levin says, “but when I last was with him — the tour ended in Japan at the end of 2022 — we had a nice talk about the future and what might happen. His words to me were that he had no plans for King Crimson doing anything else, but he would let King Crimson speak to him if it chose to. I interpreted that to mean

there are no plans and probably won’t be anything else, but it’s not impossible that there might be.”

But what there is BEAT. On September 12, Levin begins a tour with guitarist-singer Adrian Belew, guitarist Steve Vai and Tool drummer Daney Corey on tour under that moniker. They’ll be playing material from King Crimson ‘80s LPs, Discipline, Beat and Three of a Perfect Pair, with, if you’re wondering, Fripp’s blessing.

“It’s Adrian’s brainchild,” says Levin, of the musician who was in King Crimson from 1981-1984 and again from 1994-2008. “He’s been thinking about it behind the scenes and working on it for years. There were a lot of hurdles. I said a couple of years ago, ‘this sounds good’ and then time went by, trying to find the time we could safely schedule it when nobody was committed to another tour. That took a long time. When I came in, Steve was in there was in but they weren’t settled on what drummer it was going to be and I was glad they settled on Danny.”

Rehearsals start in late August. “The tour is gonna be exciting and challenging,” says Levin, “and even though I know the material I’m looking forward to the challenge of the material because two of the four are different players and this is material from the ‘80s Crimson. It remains to be seen how much things will change. I hope they change quite a bit. I will be fully on board musically and I will jump on the changes rather than insist that it be the same that it was.”